How do scientists know exoplanets exist if we can’t see most of them?

Exoplanets are planets that orbit stars outside our solar system. Most of them are too distant and too faint to be directly photographed. Despite this limitation, scientists are confident they exist because detection does not depend on seeing the planets themselves.

The core idea is simple: an orbiting planet produces measurable effects on its parent star. These effects—such as small, regular changes in brightness or motion—can be observed with precision. When such signals repeat in predictable patterns, they indicate the presence of a planet.

In this way, exoplanets are identified indirectly but reliably. The evidence comes from consistent physical interactions between stars and unseen companions, not from speculation or isolated observations.

The primary way scientists detect exoplanets: the transit method

The most widely used technique for detecting exoplanets is the transit method. It is based on careful measurement of a star’s brightness over time. When a planet passes in front of its star from our line of sight, it blocks a small fraction of the starlight, causing a brief dip in brightness.

How the transit method works

-

Astronomers monitor a star continuously and record its light output.

-

When a planet crosses the star, the observed brightness decreases slightly.

-

If the same dip occurs at regular intervals, it signals an orbiting planet.

-

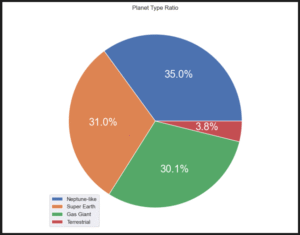

The depth of the dip reveals the planet’s size relative to the star.

-

The time between dips reveals the planet’s orbital period and distance.

These measurements rely on repeatability. A single dip is not enough. Only consistent, predictable patterns are accepted as evidence of a planet.

Instruments used

Detecting such small changes requires extremely sensitive instruments. Major space-based observatories used for this purpose include:

-

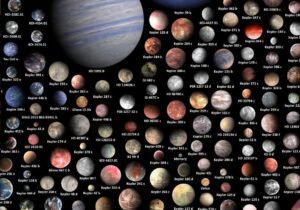

Kepler Space Telescope, which identified thousands of exoplanets by monitoring stellar brightness continuously.

-

TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), which focuses on nearby, bright stars.

-

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which studies known transiting exoplanets in greater detail, including their atmospheric properties.

These instruments do not image planets directly. They measure how starlight changes when a planet is present.

Other detection methods (briefly)

Not all exoplanets are detected through transits. Some are discovered by measuring slight shifts in a star’s motion caused by the gravitational pull of an orbiting planet, a technique known as the radial velocity method. In rarer cases, astronomers use direct imaging or gravitational microlensing, depending on the configuration of the planetary system.

Although the techniques differ, they are based on the same principle: planets reveal their presence through physical effects that can be measured.

Examples of exoplanets discovered using these methods

The detection methods described above have been used repeatedly to identify real planetary systems. Two well-studied examples show how indirect detection works in practice.

Kepler-186f — detected using the transit method

(Discovered in 2014)

Kepler-186f was identified through repeated, periodic dips in the brightness of its parent star. The depth of these dips indicated that the planet is close to Earth in size, with a radius about 10 percent larger. The regular timing of the transits revealed an orbital period of roughly 130 days.

These measurements were obtained without directly imaging the planet. The example demonstrates how planetary size and orbital distance can be inferred from starlight alone.

Proxima Centauri b — detected using the radial velocity method

(Discovered in 2016)

Proxima Centauri b was discovered by observing small, regular shifts in the motion of its parent star, Proxima Centauri. These shifts occur because the planet’s gravity causes the star to move slightly toward and away from Earth.

From this motion, scientists determined the planet’s minimum mass to be slightly greater than Earth’s and calculated an orbital period of about 11 days. No transit was observed. The planet’s existence was inferred entirely from stellar motion.

Together, these cases show that exoplanets can be detected through different signals, even when they never pass in front of their stars.

A common misconception about exoplanet discovery

A common misunderstanding is that indirect detection makes exoplanet discoveries uncertain. This assumption treats indirect evidence as unreliable, which is not the case here.

The signals used to identify exoplanets—such as repeating dips in brightness or regular shifts in stellar motion—are governed by well-tested physical laws. These signals must remain stable over time and match precise orbital predictions. Alternative explanations, such as stellar noise or random variation, fail to produce such consistency.

For this reason, indirect detection methods are considered reliable. Many areas of science rely on observing effects rather than objects directly, and exoplanet research follows the same logic.

Conclusion

Most exoplanets cannot be directly seen, but their existence is established through consistent, measurable effects on their parent stars. Techniques such as the transit method and radial velocity analysis allow astronomers to identify orbiting planets and confirm their presence using repeatable observations grounded in physics.

Detecting a planet, however, is only the first step. Once an exoplanet has been identified, a more detailed question follows naturally:

How do astronomers determine the size and mass of an exoplanet after detecting it?