How Do Scientists Determine the Size, Mass, and Composition of an Exoplanet?

Finding an exoplanet is only the beginning. Once its existence is confirmed, the real scientific work starts: figuring out what kind of world it actually is.

Because most exoplanets cannot be directly seen, their properties are reconstructed indirectly. Astronomers combine several independent measurements—each rooted in well-understood physics—to infer a planet’s size, mass, density, and atmospheric composition. No single method is enough on its own. What matters is how these measurements fit together.

The result is not a photograph or a full description, but something more careful: a constrained physical profile of a distant world.

How scientists measure the size of an exoplanet

The most reliable way to measure an exoplanet’s size is the transit method. When a planet passes in front of its parent star, it blocks a small fraction of the star’s light. That brief dimming carries precise information.

The principle is simple but powerful:

the fraction of light blocked depends on the planet’s radius relative to the star.

What is actually measured

During a transit, astronomers record a light curve—a detailed record of how the star’s brightness changes over time. From this curve, they determine:

-

Transit depth — the amount of light blocked

-

Planetary radius — inferred from that depth

-

Orbital period — the time between repeated transits

A large planet produces a deeper dip. A smaller planet produces a subtler one.

Why the star cannot be ignored

A planet’s size cannot be measured in isolation. Astronomers must first know the size of the star it orbits. Stellar radii are determined using spectroscopy, parallax measurements, and stellar evolution models. Any uncertainty in the star’s size directly affects the planet’s calculated radius.

As stellar data improves, planetary sizes are often revised. This quiet refinement is a normal part of the field, not a correction of past mistakes.

What size alone does not reveal

Knowing a planet’s radius tells us its scale, not its nature. A planet slightly larger than Earth could be rocky, rich in water, or wrapped in a thick atmosphere. Size is a starting point, not an answer.

How scientists measure the mass of an exoplanet

Mass is measured through gravity. An exoplanet pulls on its parent star, causing the star to move slightly as both objects orbit a shared center of mass. This motion is detected using the radial velocity method.

The underlying idea

As the star moves toward and away from Earth, its light shifts in wavelength due to the Doppler effect. These shifts are tiny—often smaller than a walking pace—but they are measurable with modern spectrographs.

What the data reveals

From these periodic shifts, astronomers determine:

-

The planet’s minimum mass

-

Its orbital period

-

The strength of its gravitational influence on the star

More massive planets induce stronger stellar motion. Lighter planets leave fainter signatures.

The mass is initially a lower limit because orbital orientation affects the measurement. When radial velocity data is combined with transit observations, this ambiguity is largely removed.

Why mass matters

Mass on its own does not define a planet. But paired with size, it allows density to be calculated. Density is where physical interpretation begins.

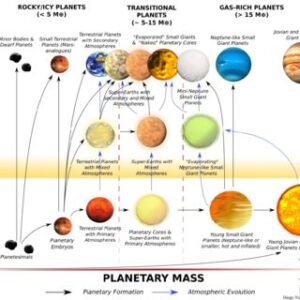

Density and composition: what size and mass reveal

Density—mass divided by volume—offers the clearest window into a planet’s internal makeup.

-

High density points to worlds dominated by rock and metal

-

Low density suggests thick envelopes of gas or volatile materials

-

Intermediate density indicates mixed structures, such as rocky cores surrounded by substantial atmospheres

These conclusions are not speculative. They are constrained by physical models tested within our own solar system.

The limits of density

Density narrows possibilities, but it does not settle them. Two planets with similar densities may have very different interiors—one rocky, another rich in water or gas. For this reason, density is treated as a filter, not a final diagnosis.

Exoplanet science advances by ruling out what a planet cannot be, step by step.

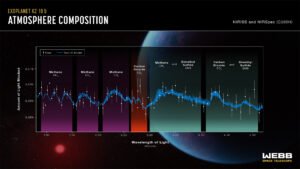

Atmospheres: what starlight reveals during a transit

Atmospheres are studied using transmission spectroscopy. During a transit, a thin layer of a planet’s atmosphere filters some of the star’s light. Certain gases absorb specific wavelengths, leaving subtle fingerprints in the observed spectrum.

By comparing spectra taken during and outside a transit, astronomers isolate these absorption features.

Using space telescopes such as Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope, scientists have detected:

-

Water vapor

-

Carbon dioxide

-

Carbon monoxide

-

Sodium and potassium in some hot atmospheres

It is important to be precise here. When water is reported, it refers to water vapor in the atmosphere, not liquid water on a surface. These measurements do not reveal oceans, clouds, or surface conditions, and they do not imply habitability.

Atmospheric observations probe upper layers only. Clouds, haze, and weak signals often limit what can be measured. Even so, atmospheric data helps refine planetary classification and guides which worlds are worth closer study.

A common misconception about exoplanet properties

A common misunderstanding is that once size, mass, and atmosphere are known, a planet is essentially “understood.” This overestimates what current observations can deliver.

Most exoplanet properties are constrained ranges, not complete descriptions. Similar densities can mask very different internal structures. Atmospheric chemistry does not translate directly into surface conditions.

The strength of exoplanet science lies in restraint. Each measurement reduces uncertainty, but none provides a full picture on its own.

Conclusion

Exoplanet properties are not imagined; they are reconstructed from measurable effects governed by gravity, motion, and light. By combining transit observations, stellar motion data, and atmospheric spectroscopy, scientists build physically grounded profiles of worlds they cannot directly see.

Each method contributes a piece of evidence, and each has limits. That caution is not a weakness—it is the foundation of reliability in the field.

Once size, mass, density, and atmosphere are known, a new question naturally emerges: what kinds of planets do these measurements describe?

Answering that leads to the next step—how astronomers classify exoplanets, and why Earth-like worlds are only one outcome among many.