Types of Exoplanets: What Size and Density Actually Tell Us

Once scientists measure an exoplanet’s size and mass, patterns start to emerge. Planets that once seemed isolated discoveries fall into recognizable groups, defined not by imagination but by measurable physical properties: radius, mass, and density.

Exoplanet classification is not about giving planets catchy names. It is about understanding how planets form, evolve, and differ from those in our own solar system. Earth is not the default outcome—it is one example among countless possibilities.

At the core, exoplanets are classified by composition and density. These measurements reveal whether a planet is rocky, gas-dominated, or somewhere in between.

Why exoplanets are classified by physical properties

Unlike stars, exoplanets emit little or no light of their own. Classification therefore relies on indirect, measurable quantities:

-

Radius — the planet’s size

-

Mass — how much material it contains

-

Density — how tightly that material is packed

Density, more than any other property, distinguishes between rocky, gas-rich, and hybrid planets. Importantly, these categories are descriptive, not absolute. Many planets sit near the boundaries, illustrating nature’s complexity.

Rocky planets: compact worlds with high density

Rocky exoplanets have high density, indicating interiors dominated by rock and metal.

Example: Kepler-10b

Kepler-10b was one of the first confirmed rocky exoplanets. Its small radius and high density indicate a solid composition without a significant gas envelope. Though far hotter than Earth, it demonstrates that terrestrial planets exist beyond our solar system.

These planets typically:

-

-

Have small radii

-

-

Lack thick hydrogen-helium atmospheres

-

Often form close to their stars or lose light gases early

Note: “Rocky” describes composition, not habitability.

Super-Earths: common, but unfamiliar

Super-Earths are planets with masses larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. They are among the most common exoplanets, yet none exist in our solar system.

Example: 55 Cancri e

55 Cancri e is a dense super-Earth with a very short orbital period. It is significantly more massive than Earth but compact, suggesting a rocky or partially rocky composition.

Typical characteristics of Super-Earths:

-

Masses roughly 1.5–10 times Earth’s

-

Radii that may indicate rocky or gas-rich worlds

-

Wide range of densities, bridging rocky and mini-Neptune planets

-

Formation paths vary; some retain gas envelopes, others are primarily solid

The term “Super-Earth” refers strictly to mass—not atmosphere, surface conditions, or habitability.

Gas-rich exoplanets

Gas-rich planets have low density relative to their size, indicating thick hydrogen–helium atmospheres.

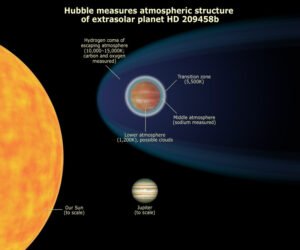

Example: HD 209458 b

HD 209458 b is a well-studied gas giant observed via transit. Its extended atmosphere is evaporating under stellar radiation, showing that even distant planets can be probed in detail.

These planets:

-

Have large radii

-

Possess substantial gas envelopes

-

Are easier to detect because of strong observational signals

Summary Table: Major Exoplanet Classes

| Exoplanet Type | Typical Mass Range | Density | Dominant Composition | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rocky planets | ~0.5–2 Earth masses | High | Rock and metal | Kepler-10b |

| Super-Earths | ~1.5–10 Earth masses | Variable | Rocky to mixed | 55 Cancri e |

| Mini-Neptunes | ~2–10 Earth masses | Low–moderate | Thick atmospheres | GJ 1214 b |

| Gas giants | >10 Earth masses | Low | Hydrogen–helium gas | HD 209458 b |

This table highlights how mass, density, and composition interact to define each category.

Why classification matters

Classification is a tool, not an endpoint. Grouping planets according to measurable properties:

-

Tests models of planetary formation and migration

-

Reveals which outcomes are typical—and which are rare

-

Reminds us that Earth is one example, not a universal template

Curiosity grows when we ask: could hybrid planets bridge these classes in ways our solar system never shows? Future telescopes may uncover these transitions